Note: Some parts of this article are necessarily vague. Nothing here is intended to reveal any sensitive “Capabilities & Methods”.

The world of security is a peculiar one. Risk cannot be eliminated completely, and even if one were to try to do this it would almost certainly result in an unusable system.

It’s all about balancing the risks against the business benefits.

But, to do this well, one needs to properly understand both the risks and the business benefits – otherwise how can they be balanced against each other?

Risk is intimately connected to probability, and probability can get complicated; combining probabilities of multiple events can be counter-intuitive.

Insider Risks

Often the most vulnerable points of a system or organisation are the people themselves. This is not a criticism, it’s simple fact. And an inescapable one1.

Real people are complex. They have complex lives. They have hopes and desires. They do unwise things sometimes. They make mistakes. They are difficult to reliably control and predict. They act irrationally sometimes. They get stressed. They get into debt. They have relationship breakdowns. Sometimes they can put themselves at risk of blackmail.

This means that you may end up with one or more Bad Actors with access to your data and/or systems. Let’s start with a definition to keep things clear:

A BAD ACTOR here means someone who is: corrupt, corruptible, or otherwise wishes to deliberately undermine the C/I/A of a system.

We’re not talking about accidents – we’re talking deliberate actions taken for a variety of motivations.

The Myth of Vetting/Clearance

I have long been worried by an attitude I frequently observe which is that someone with vetting is no longer considered an insider threat. To think like this is, frankly, a mythstake™.

It was brought sharply into focus when I once reviewed a risk document which dismissed insider risk with a phrase along the lines of “these individuals all hold SC clearance which means that they have demonstrated a high level of trustworthiness”.

There are so many things wrong with this statement that it is difficult to know where to start.

Firstly, a clearance process only weeds out “known bad” actors. It attempts to examine the individual, their history, their circumstances, and assess the liklihood of them falling into one of the undesirable categories of a Bad Actor. All it proves if an individual passes is that they’ve not shown detectable signs of being a Bad Actor or potential Bad Actor. It does not prove bona fides (good intentions), merely a lack of evidence (thus far) for mala fides (bad faith).

Secondly, some clerances last for several years. That’s a long time in someone’s life. There should be regular “aftercare” – one to one discussions about the individual & their situation, but (except for the very highest clearances) these seem to be rare indeed – I’ve seen people never receive this type of interaction over a period of twenty years or more.

FAR and FRR

There is a careful balance to be struck between the False Acceptance Rate and False Reject Rate for clearances – just as there is with the biometric systems to which these concepts are typically applied. It is inevitable that some thoroughly Good Actors will fail clearances, and that some Bad Actors will pass clearances.

The FRR is often unfortuately caused by some misconceptions and extremely outdated attitudes amongst some of the individuals carrying out clearance processes. I’ve seen an individual’s organisation being informed that the individual was “perverted” because they had revealed in a clearance process that they & their partner sometimes used sex toys. This type of 19th Century attitude has no place in the clearance process; all it does is nudge individuals towards being less open in the clearance process, and this can NOT be a good thing.

The FAR can be caused by many things. Actively hiding hostile intent, not yet being the subject of blackmail but having a weakness of character that may make them corruptible should that situation arise, and so on.

Balancing these is tricky, but necessary.

Thus we have to predicate any thoughts about insider risk with the fact that the FAR is NOT zero. And that means we have to get our hands dirty with Statistics.

Statistics are Difficult

Statistics and probability are, unless your brain works in just a certain way, confusing, difficult, and counter-intuitive.

Let’s a take a small diversion to illustrate this.

The Monty Hall Connundrum

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

Most people tend to be sure that it is a good idea to stick with their initial choice, including many people well versed in mathematics, statistics, and probability. The solution is so counterintuitive it can seem absurd but is nevertheless demonstrably true: you double your chances of winning by switching.

Quick explanation:

Consider separately the two cases of your original choice being the car, or not being the car:

You have a 1/3 chance of chosing the car initially. In this situation, changing your choice when offered will mean that you definitely do NOT win the car. So in 1/3 of cases, you will be worse off, with zero chance of winning.

You have a 2/3 chance of NOT chosing the car initially. In this sitution, changing your choice when offered will mean that you definitely DO win the car. So in 2/3 of cases, you will be better off, with certainty of winning.

This means that if you CHANGE your choice when offered, you have an overall 2/3 probability of winning the car.

If you do not change your choice when offered, you have an overall 1/3 probability of winning the car.

Does your brain ache yet?

TL;DR: There is a non-zero probability of a cleared individual being a Bad Actor

Statistics mean little applied to individuals, but applying this to groups is tricky unless you know how to combine the probabilities and – vitally – to know exactly what question you are trying to answer.

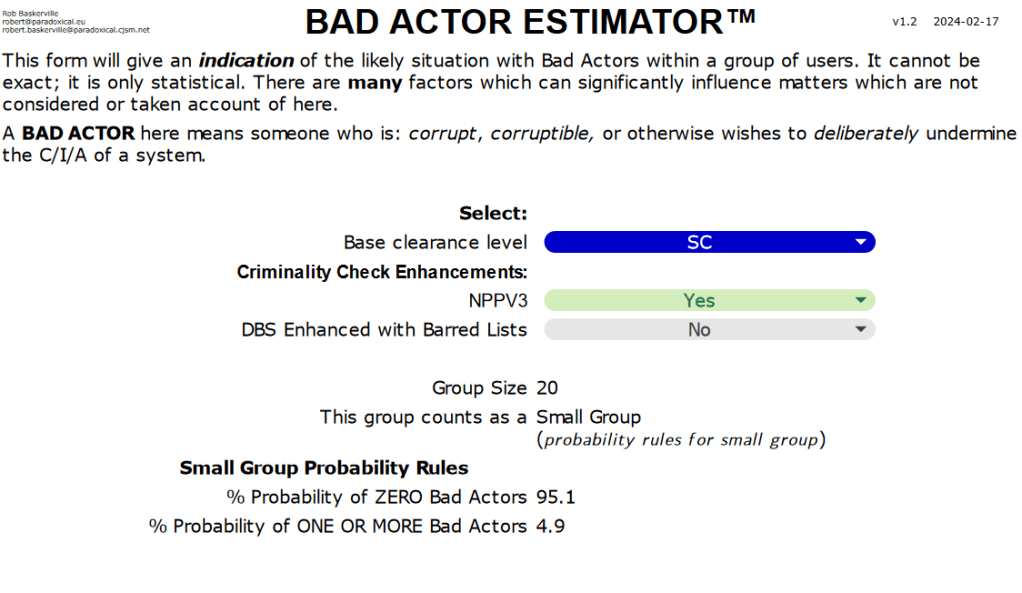

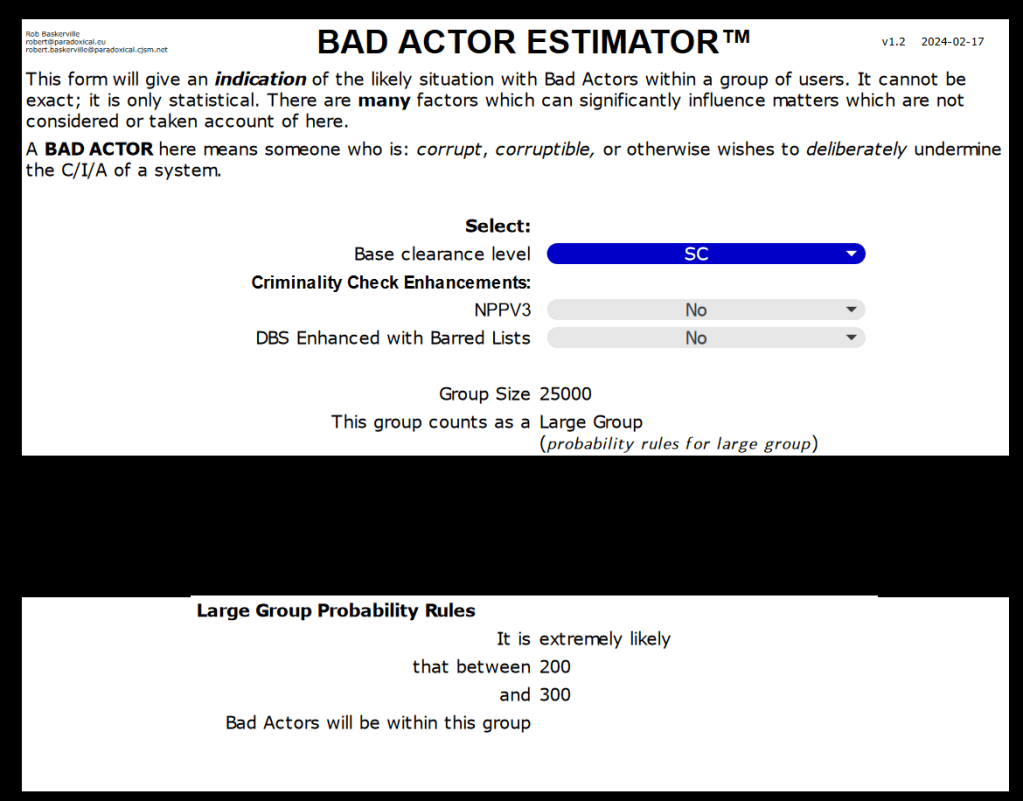

Thus for some time I have been developing, for my own use, a BAD ACTOR ESTIMATOR™ which automates the process and gives an indication at least of the probable situation with cleared groups. In order to give meaningful indications which can be applied without needing a detailed grasp of the statistics, the output comes as one of two types. For small groups2, the probabilities of there being zero vs one or more Bad Actors is given. For large groups, the probable range of numbers of Bad Actors is given.

Let’s take a look at some examples.

Group of Administrators for a Sensitive System

A group of 20 fully-privileged administrators for a sensitive system containing data relevant to Policing investigations. Each member of the group has SC plus NPPV3 clearance.

For this statistically small group of individuals, there is a better than 95% chance that there are no Bad Actors within the group. In this situation, some simple procedural controls (potentially enforced by technical means) around some of the more dangerous operations such that they require a 2-person agreement to undertake them, can provide protection against the worst likely outcomes.

Large Group of Users for a Sensitive System

A group of 25,000 non-privileged users have access to a sensitive system containing sensitive data. Each member of the group has SC clearance.

For this statistically large group of individuals, there is no realistic chance that there are no Bad Actors within the group. In fact, the most likely number of Bad Actors is in the range 200-300. In this situation, serious attention needs to be paid to the application design; the logging and Protective Monitoring design become especially important – not merely from the point of view of external attacks, but from the POV of insider threat too. Protective Monitoring needs detailed consideration in terms of what could be detected and how. Regular dip-sampling of logs may also be in order too. For this particular system, the design must cope with a significant number of Bad Actors as users – but this fact must be realised or it will not be designed & run that way.

The BAD ACTOR ESTIMATOR™ is currently in beta-testing with a few individuals. If there is interest, it may be made more widely available.

Footnotes

- Donald Maclean. Guy Burgess. Kim Philby. Anthony Blunt. John Cairncross. Geoffrey Prime. Klaus Fuchs. George Blake. Enough said, really. ↩︎

- What defines a small vs large group? The statistics! The boundary between small and large will depend upon the nature of the clearances held. If the probability of there being NO Bad Actors in a given group is too low, the group gets considered as a large group. ↩︎