MFA is becoming ubiquitous for many of us. I’d like to:

- Highlight a rarely-considered risk with using MFA

- Explain how this can be exploited

- Give advice for how to avoid your users be exploited in the fashion

You what?!

So before we get down to subverting some extremely useful and important technology that provides MFA, we should probably define some terms.

- Insider

- Someone who is part of your organisation

- Nearsider

- Someone who is not part of your organisation, but has good access to it, typically through

- Location: a neighbour to your business premises or home

- Personal Relationship: a domestic partner for example

- Not a comprehensive list – just indicative

- Someone who is not part of your organisation, but has good access to it, typically through

- Outsider

- Anyone at all who is neither an Insider nor a Nearsider

- MFA

- Multi-Factor Authentication. Here we’re specifically looking at time-dependent tokens: TOTP, Time-based One Time Passwords; the authenticator apps we all need to use now

- Subversion

- If we can subvert TOTP MFA, we manage to acquire the secret. This gives us access to the MFA challenges any time every time.

But MFA is secure, right?

Security is a fascinating area. It’s full of edgecases and devil-in-the-detail situations. Sometimes one needs to look at the bigger picture to really understand what does, and does not, make security sense.

A Short Crypto Detour

Modern cryptography tends to rely upon public algorithms, with all of the security dependent upon the key rather than secrecy of an algorithm. Of course, those algorithms might have weaknesses. There is just one type of encryption which cannot possibly have this type of algorithmic weakness.

One-time pad (OTP) encryption is renowned for having a what is known as perfect secrecy, a term coined by mathematician and cryptographer Claude Shannon in 1949, and meaning that a ciphertext reveals NO information about its corresponding plaintext other than its length. It does not matter how much ciphertext you gather up to analyse; it could decrypt to literally anything depending upon the key.

So why doesn’t everyone use OTP all the time every time? Well, bluntly, because it’s incredibly expensive and inconvenient. You see, the encryption is perfect in its security, but all the problems have been shifted elsewhere – in this case, to creating and managing the key material – the one-time pads.

Firstly, your key material has to be the same size or larger than what it is that you wish to encrypt. So for a 1 GiB file you need 1 GiB of key material. That’s quite significant cf a typical 256 bit keysize for symmetric encryption algorithms.

Secondly, the key material must be truly random – very high quality entropy. If you generate the keystreams algorithmically, then that algorithm introduces predictability and thus weakness. This is expensive, because true randomness is difficult and you probably have to rely upon radioactive decay or cosmic background radiation to drive high-quality entropy. Government high-grade cryptography often only differs from commercially available cryptography by the assured quality of the key material entropy and the assurance of the key management.

Thirdly, you can only use each piece of key material once. OTP – One-time pad; clue’s in the name. If you re-use the key material then you introduce a massive weakness that can blow the security wide open. Suitably combining two ciphertexts produced using the same key material results in the two plaintext messages mangled together (imagine two plain language texts XOR’d together). Since the entropy of English text is between 0.6 and 1.3 bits per character of the message, there is plenty of redundancy available to enable recovery in most cases of both texts.

Of course, no one is really going to actually notice re-use of key material, right?

Wrong. Because it is so expensive to use, it is only used for certain traffic, such as diplomatic traffic, with key material shipped around by diplomatic couriers. This type of traffic is naturally a target, and one which State Actors are prepared to expend significant resources against.

Through a combination of problems at a Soviet company that manufactured the one-time pads (resulting in around 35,000 pages of duplicate key numbers being issued simply to keep up with the demand for key material), and some brilliant cryptanalysis, it was noticed, and messages were broken or partially broken as a result. This was Project Venona, and Wikipedia has an excellent overview and explanation of it and how important were the secrets thus revealed – and we’re talking really serious stuff. There are actual message extracts of soviet diplomatic traffic recovered by this project on the NSA’s Project Venona pages.

OK, so I lied about the “short” detour. But the point is: if something claims to be VERY secure, then you need to understand the downsides of this; is it unusable? Have the problems merely been shifted into a different area?

OTP encryption is perfect. But it creates a simply massive key material generation, management, & distribution problem. Remember, as ever with assurance, you have to ask the right questions to reveal where the weaknesses may be lurking.

MFA TOTP Security

So let’s remind ourselves about how TOTP provides secure MFA.

TOTP uses public algorithms. The time, upon which the output depends, is hardly a secret. But in addition to these elements, there is also a SECRET. The algorithm combines the time with the secret to produce a “tokencode”, a one-time passcode.

Authenticator applications put significant effort into guarding those secrets, because if anyone else has the relevant secret, then they can trivially fake-up the MFA. But they have to obtain the secret first!

You Are The Weakest Link… Goodbye

Having the secret burried deeply within an Authenticator App is fine. But how does it get there?

Enrollment into a TOTP system is typically done via a QR Code displayed on the user’s screen. And herein can be found the weakness.

Here’s an annotated example from Microsoft’s support pages

Can you see what is missing from this page? I’ve seen more of these pages than I care to remember, and every single one had the same thing missing from it:

“There is no warning anywhere whatsoever about the dangers of shoulder-surfing or leaving this QR Code on display for more than the absolute minimum of time.”

— Me, 2024

Personally I’d like to see a big “check no one can overlook your screen, prepare your authenticator app then press here” type button before the QR Code is even revealed.

But no one is actually going to grab the code from behind you, right?

Wrong. I did some experiments during the pandemic lockdown and was amazed how far away I could capture the image from, using a monocular and a phone with a decent camera. I’ll tell you how far later. This puts the MFA at risk of subversion by Insiders and Nearsiders.

Let’s ̶E̶n̶c̶r̶y̶p̶t̶ Steal The Secret

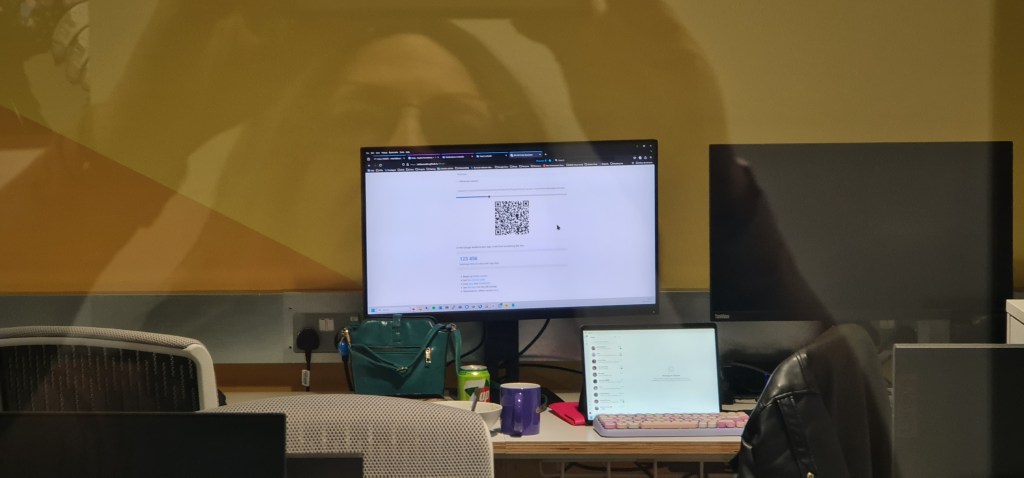

Today we repeated these experiments using JUST the camera on a reasonable smartphone, to show you just how vulnerable this enrollment process can be. Photographs by Sophie, in this case being a Nearsider with only a view through a high unfrosted pane in an office window, and about 10 metres from the monitor displaying the QR Code.

The plan was for her to photograph the monitor and for us to later see if we could extract the QR code, with its embedded secret, from one of the photographs. Turns out it was simpler than that.

We’ll start with the photo she took from outside of the office through the window. There’s the monitor plus QR code right in the middle, seen through a high un-frosted pane. Not usable from this wide-angle shot (zoom factor = 0.5), but this is really to give you an overview of the distances involved:

Default mode photo (zoom factor = 1). Say “hi” to Sophie’s reflection:

Now this is more like it. The QR tokencode is clearly visible, if a little small. Zoom factor 5x (optical not digital zoom):

Adding in 4x digital zoom on top, giving 20x in total, and we can really see the QR code pretty well. Maybe we’ll be able to extract the secret from this later:

Oh… wait! The phone has already done it for us! We’ve won, and the security of the MFA has evaporated (phone screenshot below):

At first look, it might appear as though we’ve broken the MFA reducing us back to single-factor username/password to break. But really, it’s worse than that because once MFA is in place, the password security tends to be neglected – the requirement to change the password regularly is lowered or even dropped altogether. Remember, it’s supposed to be Defence in depth, not Defenceless and shallow.

“To MFA or not to MFA, that is the question”

So should we bother with MFA? Yes, absolutely. This is an attack that only works at enrollment time. It doesn’t help outsiders – only insiders/nearsiders.

“We should be warning users to be careful, and to do that effectively the users need to understand the significance / criticality of that QR Code at enrollment time.”

— Me, 2024

Then maybe we will have better assurance around the strength of our MFA authentication, and better defence against both insiders and nearsiders.

And for reference: with a monocular plus a smartphone camera, I was able to steal a QR code from a monitor in excess of 100m distant.

One response to “Insider/Nearsider Subversion of MFA”

[…] previous articles, I’ve talked about insiders, outsiders, and nearsiders. The insider risk here arises if this is an area within an organisation’s building which is […]

LikeLike